Prescribing Canadian-Style Healthcare

Originally published in Synapse - The UCSF student newspaper March 5, 1992.

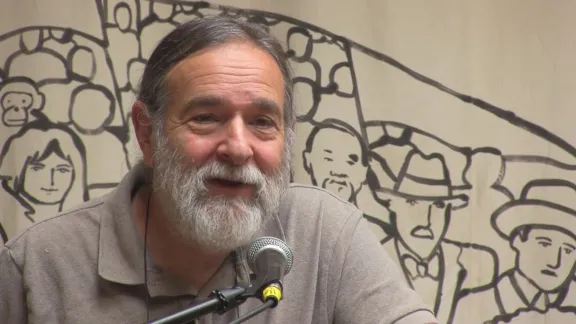

Dr. David Himmelstein, founder of Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), promised that “something rather straightforward and simple can be done to save the United States healthcare system.” That something, he thinks, is a Canadian-style national health plan similar to the Russo bill being proposed in the House.

He outlined the shortcomings of the present system — and some possible solutions — at a Feb. 21 talk presented by the School of Nursing.

Most Americans now favor national health insurance, according to Himmelstein. He cited statistics showing that two-thirds want a plan similar to Canada’s.

Physicians, too, are ready for a change, Himmelstein reported; 89% would accept a 10% decrease in their incomes in return for a decrease in their billing and insurance paperwork.

Expenditures for healthcare have been increasing steadily for decades and now comprise 14% of the GNP. Himmelstein points out, however, that until the late 1975, increasing costs were mirrored by increasing insurance coverage.

He feels the current crisis has resulted from a reversal in coverage trends that have left increasing numbers uninsured. Even those who are insured have problems getting the care they need due to financial constraints such as copayments, deductibles or inadequate coverage.

Quipped Himmelstein, “The image of our health insurance coverage is a little bit like a hospital gown. The coverage looks all right up front but once you get around to the back it leaves a fair amount to be desired.”

Given that one-third of all hospital beds are empty, that substantial numbers of unnecessary procedures are regularly performed and that a vast surplus of equipment such as MRI and mammography machines exist, the lack of access to care is not due to a lack of resources.

Himmelstein explained the contradiction, “In effect, our policy has been focused on rationing a surplus of resources... It takes a great deal of effort to keep sick patients out of empty hospital beds. So, we have had a rapid growth of the bureaucracy needed to perform that task.”

Himmelstein’s solution: reduce bureaucracy and therefore costs by eliminating private insurance and adopting a national health insurance system similar to Canada’s. In Canada, all citizens are covered for all medically necessary services (as defined by the individual provinces) with virtually no co-payments or deductibles.

The program is administered on a non-profit basis, which is more efficient and less costly than private administration. For example, in the U.S., overhead and profits for private insurance companies account for $45 billion or 15 percent of total premiums.

In Canada, overhead accounts for 1 percent of the total cost.

“For any given level of health spending,” Himmelstein asserted, “Canada gets far more clinical care than we do.”

Himmelstein pointed out that the tax burden for Canada’s system is similar to what Americans already pay and that the proposed plan could be implemented by spending the same proportion of GNP that is now being spent.

By eliminating private insurance, Himmelstein foresees a savings of $27 billion. Hospitalization expenditures would remain unchanged. The net savings for the National Health Plan would total $18 billion per year.

This could then be spent on instituting insurance for long term care, which is the most rapidly growing segment of health care expenditures, and to pay for the actual implementation of the plan.

In addition to political stumbling blocks, Himmelstein acknowledges a number of drawbacks with the PNHP plan. Number one among them is the transition to the plan.

Some 400,000 persons working in the private insurance sector would be unemployed. Himmelstein referred to a possible GI-type bill to retrain these workers, but noted that it has not been written into any of the bills in Congress.

Nor did Himmelstein address the specifics of transforming the health care system, which services would be covered, who would decide what is covered, which agencies would administer it.

Alternative Approaches Himmelstein evaluated the four most viable healthcare alternatives being looked at in Congress. Of these, he supports die Russo bill, which he described as a Canadian-style program embracing 95% of what the PNHP has proposed.

The “Pay or Play” or Kennedy-Mitchell bill would require employers to either buy insurance for employees with minimum benefit packages or pay a tax to the government that would be earmarked for a new program called Health America.

Himmelstein views this as the renaming of Medicare and Medicaid with retention of the two-tiered system of care.

“There is only one reason for there to be a private system,” Himmelstein said, “and that is if the public system is worse.”

In addition, because it leaves in place all existing private insurance arrangements and adds to it a public program, the Pay or Play plans are administratively expensive and complex.

Massachusetts passed its own P-or-P in 1988 and has implemented only the portion of it, which covers those who receive unemployment compensation; 40% of funding has gone to administering it.

Regarding Bush’s proposal, Himmelstein commented, “I’m not sure I really want to dignify it by calling it an option. But it’s out there.”

He went on to explain that it calls for tax credits and tax breaks for private insurance to be funded by taking money out of Medicare and Medicaid.

“Think about it,” Himmelstein sarcastically explained, “Medicare has an overhead of 3% of premiums. Medicaid 4%. So what he [Bush] is saying is we are going to take $100 billion out of Medicare and Medicaid and use it to subsidize insurance, which has a 15% overhead. What that means is he’s giving a $12 billion gift to insurance companies and making $12 billion less available for clinical services than at present.”

The last proposal — managed competition — is the most viable in Himmelstein’s opinion. This approach has the support of large numbers of Republicans and the New York Times and will soon be introduced in Congress.

Managed competition calls for five or six very large HMO’s which would compete based on price. A tiered system may again result, according to Himmelstein, because there might be one or two inexpensive HMOs for the poor, a couple of middle-priced ones for the middle class, and one top-of-the-line HMO for the wealthiest 10% of the population.

The incentive to make a profit at the expense of providing quality care to everyone (including the unhealthy) also concerns Himmelstein.

Currently, most managed care organizations, with the exception of Kaiser, are owned by insurance companies who make a profit not by providing more efficient care, but by manipulating enrollments so that only “healthy” people belong to the group.

Besides, he reminded the audience, Americans value their freedom to choose medical providers, and in a managed care system, the choice would lie largely with employers.

Himmelstein predicts that none of these plans will pass this year. He foresees minor insurance reforms such as a requirement that insurance companies cover people with preexisting conditions.

“If you include people with preexisting conditions who are currently uninsured,” says Himmelstein, “you increase premiums about 15% for those who are insured and probably drive as many of them out as you bring new people in.”

Himmelstein’s biggest fear is the passage of a watered-down bill which will not work. The liberals will then be faulted and any progress which had been made will be reversed.

Remembering the hits the liberals took for Medicare and Medicaid, Himmelstein exclaimed, “I’d hate to be put back in that position, so let’s pass something that is defensible.”