This Date in UCSF History: Beyond Vietnam

Written by Dr. Toan Truong while interning in medicine at UCSF and published in Synapse on May 17, 1990.

The producers of “Beyond Vietnam,” an ABC News/Time forum about the prospects of normalization of diplomatic relations with Vietnam broadcast on April 26, called me at the hospital.

They had read a commentary I wrote for Synapse (and The New York Times) in February and wanted to invite me to be part of the panel discussion. It is not often that a Vietnamese American gets to make his views known to a national audience, so I accepted provided I could get the time off from my duties at the hospital.

It was easier than I thought. I quote my attending physician: “Toan, be sure and tell the audience that you are grateful to Dr. Tom Dewar, your ‘studly’ and good-looking attending who is letting you off to go to New York but be sure to come back by Friday because you are on call on that day.”

I did not spend too much time wondering about the logistic of being on the air live past midnight the day I am supposed to be on call across the continent.

There I was, flown to New York at ABC’s expense, and whisked to the Plaza Hotel, now managed by Ivana, herself a marvel of cosmetic surgery, newly featured in the April issue of Vogue — copies were prominently displayed in every room in the hotel.

At the studio, anchorman Peter Jennings said he enjoyed my article and would be calling on me when the time came.

To my considerable surprise, I found out that I was not part of the main panel. This meant that I had to sit in the front row with the audience and my microphone would be turned on only when he asked me a direct question.

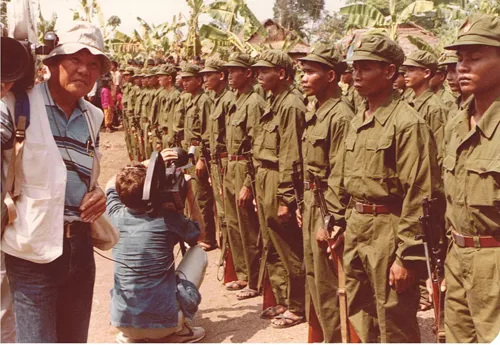

For the first hour, we watched a documentary entitled “Peter Jennings Reporting: From the Killing Fields” as it was being broadcast live.

The main point the program tried to make was that the Khmer Rouge, who murdered one million Cambodians during the three and a half years they ruled the country, are poised to regain power and the United States is promoting this return.

We are apparently doing this by indirectly providing them with lethal and nonlethal aid through the noncommunist resistance. The evidence presented was circumstantial at best.

The documentary suggests that the noncommunist resistance is cooperating militarily with the Khmer Rouge. This was demonstrated through a film clip showing a Khmer Rouge soldier holding the hand of a noncommunist resistance fighter.

When one thinks about it, this is evidence of nothing. Most of the soldiers fighting today are too young to remember the “killing fields.”

Khmer Rouge and noncommunist soldiers from the same regions may fraternize whether or not there is real military cooperation.

The panel discussion that followed was a disappointment to me for many reasons.

It was unfortunate that a panel which would discuss the prospects of renormalization of diplomatic relations with Vietnam only had one Vietnamese out of 20 panelists.

I do not include myself because I was not part of the main panel and was never allowed to speak.

The program was almost entirely a follow-up on the prior documentary. Battle lines were drawn quickly, dividing the panelists into factions.

The politicians were busy refuting Peter Jenning’s accusations and maintained that the solution to the crisis is a fair and free election in Cambodia supervised by the United Nations.

The women on the panel confirmed that the Cambodian people are the real victims — no big surprise there.

The two Cambodians on the panel wanted everyone out of Cambodia, including the Vietnamese, Russians, Americans and Chinese.

The whole discussion was punctuated by unrestrained outbursts from a veteran who seemed to have a grudge against the Establishment (represented by the politicians and General William Westmoreland), and by actress Liv Ullman, who provided the chorus by periodically shouting “What about the children?”

The human suffering should add a degree of urgency to the negotiations, but one cannot escape the fact that an essentially political problem demands a political solution.

Watching white people sit in armchairs decide what is to be done with Cambodia made me think back to the Vietnam War.

This was exactly what was happening to my poor country: a bunch of people in the White House, in Congress, in the Kremlin, in the Forbidden City deciding its fate regardless of what the Vietnamese people wanted.

The media tends to focus on what the U.S. is doing wrong rather than what we are doing right.

The U.S. has now thrown its full support behind the Australian proposal which calls for the U.N. to administer the country during an interim period leading to an internationally supervised free election, à la Nicaragua.

The architect of that policy is congressman Steven Solar, D. Brooklyn, who was part of the panel. He truly is the Cambodian people’s best friend in America.

It was sad to see him being made to sound like a dishonest politician that night. In what was a two-hour show, the last half hour was devoted to Vietnam and part of that time was taken up by old footage.

The question of whether the United States should normalize diplomatic relations with Vietnam was posed to various panelists.

Ex-ambassador Bui Diem skirted the issue altogether. Westmoreland and a student from Dartmouth University thought that it will have to wait until the problem of the MIA/POWs is resolved.

This is so typical of our attitude towards the rest of the world. Most of the time, we only care about the world only in so far as “our” direct interests are concerned.

If I could have spoken, I would have challenged Americans to think about what the Vietnamese people are going through.

I myself would wholeheartedly support not only diplomatic relations with Vietnam and the lifting of the embargo, but also economic aid for the country if its government would fulfill the following requirements:

Close all reeducation centers and “New economic zones,” and release all remaining political prisoners.

End the policy of “indefinite detention” and guarantee the right for a fair trial to all prisoners.

Abolish all institutions enforcing the police state, mainly the Family Residence permit and the Precinct Security Cadre.

Guarantee freedom of the press, speech, thought, religion, movement, association and congregation, and the right to observe a religious life without harassment.

Relinquish the “leading role” of the Communist Party and let all political, religious, and social elements participate fully in the reconstruction of Vietnam.

Release the poet Nguyen Chi Thien and the Buddhist monk Thich Tue Sy as a token of good faith. To normalize diplomatic relations with Vietnam without conditions means condoning violence and repression against its people.

I hope that one day it will rejoin the community of nations in an era of peace, prosperity, and democracy.

Let our foreign policy with Vietnam be guided by this vision and the suffering of the Vietnamese people may finally come to an end. Let me conclude with an excerpt from Nguyen Chi Thien’s smuggled manual: My poetry’s not mere poetry, no, but it’s the sobbing of human life, the clang of doors in a dark jail, the wheezing of two poor wasted lungs, the thud of earth tossed down to bury dreams, the clank of hoes that dig up memories, the clash of teeth chattering from the cold, the cry of hunger from a stomach churnin’ wild, the throb-throb of a heart that grieves forlorn, the helpless voice before so many wrecks, All sounds of life half-lived, of death half died — no poetry, no.