This Date in UCSF History: Parasitic Attraction

Originally published in Synapse on March 22, 2007.

Recent data suggests that latent infection with Toxoplasma gondii, commonly thought to be a relatively benign parasite, causes far reaching and subtle behavioral effects.

According to an article written by Dr. Nicky Boulter in the December 2006 issue of Australasian Science, “infected men have been shown to have lower IQs, achieve a lower level of education and have shorter attention spans.

“They are also more likely to break rules and take risks, be more independent, more anti-social, suspicious, jealous and morose and are deemed to be less attractive to women.

“On the other hand, infected women tend to be more out-going, friendly, more promiscuous and are seen as being more attractive to men compared with non-infected controls.”

The most compelling study conducted by Lindova et al. examined the behavior of 92 male students and 171 female students at a university in the Czech Republic.

Participants consented to serological testing to assess the presence of anti-Toxoplasma antibodies, completed an extensive personality survey, and participated in a one-hour double-blind experiment conducted by the same female moderator.

The moderator scored participants on every aspect of the interview, such as punctuality, responses to questions assessing social networks, personal appearance and clothing (on a 1-5 scale), willingness to drink a mystery substance (under the false premise of assessing the ability to taste a bitter compound), and willingness to be photographed.

While infected males achieved significantly lower scores in areas of “relationships,” “self-control,” and “clothes tidiness” compared to uninfected men, infected females were more likely to exhibit higher scores in these areas than their uninfected counterparts.

A similar trend in behavioral changes has been observed in mice infected by T. gondii according to studies conducted by Berdoy et al.

Infected and uninfected mice were placed in boxes containing four areas containing distinct scents: mouse urine, neutral straw, rabbit urine, and cat urine.

Infected mice were significantly more likely to spend more time loitering around the area scented with cat urine than uninfected mice.

The authors postulate that this behavioral change leads to increased feline predation of infected mice, allowing the parasite T. gondii to complete its reproductive cycle in the cat.

Although the parasite’s effect on infected mice may be explained in this manner, it becomes less clear why T. gondii would benefit from the behavioral changes observed in infected humans, or why men and women may be affected differently.

Lindova et al. suggests an intriguing theory to explain the difference in gender-based outcomes, proposing that infected males who exhibited risk-taking and antisocial behavior in a pre-civilized era would become more vulnerable to predation (perhaps by lions and tigers, no bears), allowing the parasite to spread.

On the other hand, infected women who behave in a more outgoing, social, and promiscuous manner would have a higher likelihood of mating and passing on the parasite to their offspring.

T. gondii is transmitted to humans through the ingestion of infected cat feces or undercooked meat and may significantly affect the behavior of infected individuals in a gender-specific manner.

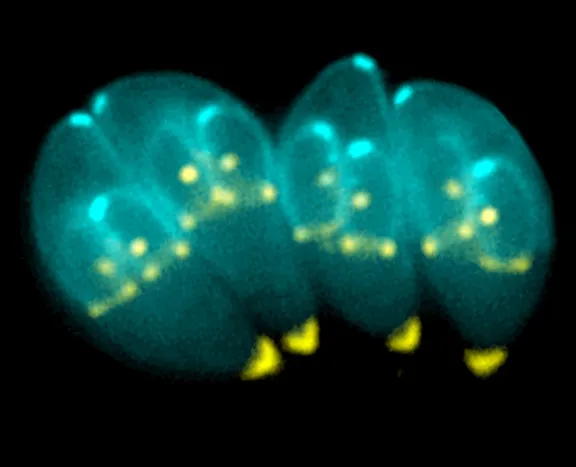

Although approximately 2.5 billion people (roughly 40% of the world’s population) are estimated to be infected with T. gondii, the parasite typically remains contained by a healthy immune system and takes up permanent residence in the brains and musculature of infected individuals in the form of inactive cysts.

No treatment exists for these cysts, but the parasite is usually only considered a danger to pregnant women or immunocompromised patients. Infection with T. gondii has also been correlated with higher incidences of schizophrenia.