A Look Back at AIDS Research Pioneers

As a healthcare provider, I was taught to follow protocols and look for information, patterns, and pathognomonic criteria to identify diseases.

Although you must indeed be wise and be attentive to any sign in patients, because there are no absolutes in health care, I had not felt so much uncertainty as I have experienced as a researcher.

Uncertainty gets along with the science — this disarray for the unknown and the simultaneous curiosity to find answers — is part of the game.

Healthcare providers and investigators have been struggling with uncertainty for two years because of the COVID-19 outbreak. However, much of the knowledge that guided them during this challenging period was established 50 years ago, when healthcare providers faced another unknown — the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Dr. Deborah Greenspan and Dr. John Greenspan are role models in the fields of medicine and dentistry. They were at the forefront of AIDS research. Dr. John listed numerous reasons he wanted to get involved in the research.

“Probably the challenges, the opportunity to help people in need, the prospect of discoveries beyond the fog of ignorance and stigma, even against some institutional resistance,” said Dr. John.

Both were born in England and studied in the Royal Dental Hospital of London, School of Dental Surgery. Dr. Deborah focused her career on Dental Care, and Dr. John specialized in Oral Pathology.

“I enjoyed my dentistry studies and clinical work,” he said, “but soon reverted to the intellectual basis of my bachelors studies in anatomy, and having worked in that area briefly realized that its extension into disease really captivated my interests. So, I turned to general and oral pathology.”

They came to San Francisco in 1972 during a sabbatical year for Dr. John, who worked as an associate professor at UCSF.

“When we emigrated, I moved into working with Dr. Troy Daniels, Dr. Sol Silverman, and the faculty of the oral medicine clinic, mostly on patients with oral problems post-cancer care. I found that experience a wonderful one,” said Dr. Deborah.

Then, when they returned a few years later, Dr. Deborah pursued the oral medicine residency.

“During the next two years [1976-1978], I did a fellowship in oral medicine,” she said. “My interests were in cancer and cancer therapy problems, so some of my early interests were in the side effects of radiation therapy on the head and neck and the consequences of that therapy. I was also interested in the treatment results for other malignancies.”

Meanwhile, Dr. John worked as a professor in Oral Pathology and became the founding chairman of the UCSF Division of Oral Biology. So, when AIDS came along, they participated organically.

“Deborah was seeing a number of young men with oral candidiasis as early as 1978,” he said. “As soon as the new syndrome was identified in 1981, she realized that there was overlap between her group of patients and those being seen in Dr. Marcus Conant’s clinic with what was later named AIDS.”

A side effect of radiotherapy in head and neck cancer patients is oral candidiasis.

This fungus infection originates from commensal oral microbiome species due to the increment of immunosuppression. It develops a white pseudomembranous patch that can be removed easily, leaving a red surface.

During that time, Dr. Deborah was also seeing patients who had unmovable white patches in the mouth that were not responding to antifungal therapy.

“A non-removable white patch in the mouth is called leukoplakia,” she said. “Some of these leukoplakias may represent dysplasia or early squamous cell carcinoma. For example, in 1981, I saw people with white lesions on the tongue that were thought to be due to candida that didn’t respond to antifungal therapy.

“So, therefore, we biopsied them because we need to find out what they are and ensure no dysplasia or carcinoma.”

At about the same time, Dr. John was among the pathologists at UCSF who diagnosed the first local cases of AIDS lymphoma.

Due to his work reading biopsies, Dr. John diagnosed a Burkitt-type lymphoma from a nodule present in the mouth of a young man.

Lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma had already been reported in kidney transplant patients. Thus, he thought that something similar might happen with the immunodeficiency of gay men.

His theory was corroborated once the referral colleague confirmed the risk factor of the patient. Dr. John had been found the first case of lymphoma in an AIDS patient.

Dr. John said they were both stumped about the histopathological findings — that the biopsies obtained from the white patches that didn’t respond to antifungal therapy located in the lateral tongue of the AIDS patients.

“So we agreed that she should biopsy several examples, and I would look for Candida, Human Papilloma Virus, and other viruses,” he said.

“He found a peculiar histopathology and a herpesvirus on electron microscopy and soon showed it was Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), working with Dr. Evelyn Lennette and with Dr. Harald Zur Hausen’s group in Germany,” said Dr. Deborah.

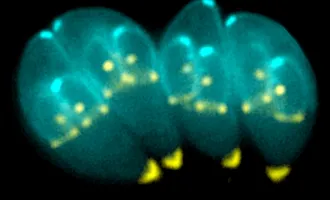

That peculiar feature that Dr. John observed was nuclear clearing and peripheral chromatin margination in the upper layers of the epithelium.

He had identified “the ballooning cells,” the expression of EBV co-infection in the oral mucosa.

These cells were the pathognomonic feature of hairy leukoplakia — the corrugated white vertical patch in the lateral tongue that had not responded to antifungal therapy seen in the AIDS patients.

They, for first time, described an oral mucosal lesion, which allowed understanding of the natural history of HIV disease and its association with other oral lesions such as candidiasis, HPV lesions, and Kaposi’s sarcoma.

In addition, Dr. Deborah introduced rational, safe infection control protocols in the School of Dentistry, pushing UCSF at the forefront nationwide, demystifying the disease, and striving to eliminate the stigma that these patients often encountered when seeking dental care in the community.

Meanwhile, Dr. John started to collect biospecimens in 1982 with the help of Dr. Marc Conant, Dr. John Ziegler, and NCI funding. They founded the UCSF AIDS Specimen Bank (ASB).

Dr. John established the ASB with Yvonne DeSouza in late 1982 at the request of Drs. Marcus Conant and John Zeigler, the then-effective leaders of the UCSF AIDS/HIV effort.

“We have accessed over 1 million specimens and have sent out even more,” he said. “Dr. Richard Jordan and Salman Mahboob currently lead the ASB, and they have extended into COVID studies. I am still a consultant.”

I wondered if they faced any confusion or hesitation about what path to follow during those days. How did they know which direction to take?

“We remember little if any confusion or hesitation, apart of course from seeing so much new or at least unusual pathology, so much of it in young men, many of whom in those early days were likely to die,” Dr. John said.

“Moreover, we were privileged to have so many expert colleagues who we could consult when we met such challenges.”

Forty years later, Dr. John lists their legacy of accomplishments in oral pathology and oral medicine related to HIV/AIDS.

“The discovery of hairy leukoplakia, its association with EBV and AIDS; the crucial importance of optimum oral care for this group; the need for all dentists to wear gloves and use universal infection control for all procedures; the medical/dental link.”

The latter was an outstanding contribution — physical barriers to avoiding infectious diseases were a crucial protocol, and it was applied in the subsequent disease outbreaks.

“Our AIDS/HIV work has been widely explored and commented on. However, in those years of the early 1980s, that work was a fairly small part of what we were doing,” Dr. Deborah said.

“We knew that we were part of a tiny group at UCSF and elsewhere working in the field,” added Dr. John.” We felt real excitement, a desire to help and, to be frank, that we were probably part of something historic.”

Their work also provided healthcare providers with numerous lessons.

“We learned many lessons during AIDS outbreak,” Dr. John said, “the importance of interdisciplinary team science; the value of well-characterized patient cohorts with associated fully documented biospecimens; the need to work across boundaries, nationally and internationally; the importance of educating oral health professionals about AIDS/HIV, infection control and the need to overcome stigma; the need to educate a full range of non-dental health professionals about oral diseases, notably those of AIDS/HIV; the value of working with funding agencies, notably NIH of course, to develop funding streams; and how important it was to learn from ethicists and medicolegal experts about the interface between what we were doing and their fields.”

.