X-rays and Seeing

Before I ever came near a stethoscope or a white coat, I understood the beauty of X-rays. The reasoning was simple, nearly elegant. If we could just take a picture of the inside, we would know what was happening. As a child, this logic was flawless. Our playground worlds glittered with X-rays and the colorful casts that followed them (though I speak not from personal experience).

But like many things we look back on with nostalgia, that logic was incomplete. Much like believing in Santa Claus or that swallowing watermelon seeds would grow fruit in our bellies, the truth is: X-rays are not the only way to see inside the human body.

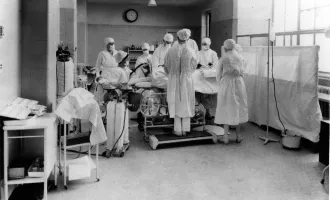

In medical school, I have learned there are many ways to see. We have an entire arsenal of tools beyond X-rays: ultrasounds, CT scans, MRIs, even nuclear imaging if we’re being fancy. There’s a whole field dedicated to the act of capturing images of the human body: radiology.

From pre-clinical coursework to clinical rotations, I’ve spent countless hours trying to master the art of “seeing.” These lessons have taught me that while in life we often say seeing is believing, in medicine, seeing is itself an art — and sometimes a matter of life or death. The method we choose to see with can mean the difference between catching a growing mass or missing it entirely. It’s not just about looking, but looking carefully, and with the right tools.

Unfortunately, outside of medicine, despite its importance, most of us are never formally taught how to see. Of course, there are disciplines like history or literature that ask us to “close read,” to open the space between words and find meaning in what’s left unsaid. I know this well. I spent years studying the history of science and medicine, learning that the supposed objectivity of medicine is only part of the story.

But what happens after we leave school? We begin to rely on the world to teach us how to see through a haphazard mix of personal experience, media, and half-told stories. It’s almost as if someone else puts the glasses on for us. And rarely are we even handed a tool by which to see for ourselves.

Why should we care about this?

Well, I care because I’m afraid. I’m afraid of a world that doesn’t know how to see and more frightening still, a world that refuses to see how systems and -isms quietly warp our vision. I worry about the erosion of spaces where we once learned to read critically, think freely, and question responsibly.

I’m concerned we’re losing the language to describe what we see, given the growing restrictions on critical discourse. This ties hand in hand with the slow decline in literacy rates we are seeing across the nation. In summary, we are often asked to look at only X-rays and because of that, we lose more than half the story. As we might say in the hospital, we miss the diagnosis.

I encourage you to train your brain to see the other “imaging”. It’s there that we begin to uncover complexity. It’s how we challenge assumptions about the world we’ve taken for granted. It adds valuable dimension to the story from which we build true solutions to societal challenges.

This is a lesson I’m still learning. As a (hopefully) future internal medicine doctor, I will be charged with seeing pathology in the hospital, but I will be a better doctor to my patients if I can also “see” the world’s pathology — in our systems, our institutions, our narratives.

This is because medicine is not separate from the world. And learning to see, truly see, is one of the most urgent responsibilities we carry.