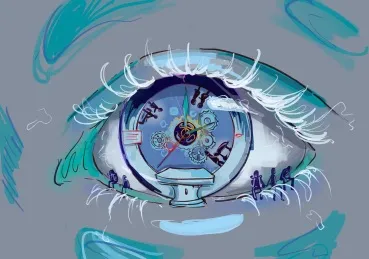

Confession of the Eye

“Confession of the Eye” is a narrative commentary that reflects on a personal encounter in the emergency department to explore the broader systemic challenges within the U.S. healthcare system, particularly in under-resourced settings. Using a patient’s delayed stroke care as a lens, the piece examines themes of overcrowding, healthcare inequity, and the emotional toll of systemic inadequacies on both patients and providers. The approach is reflective, drawing from lived experience and anchored by relevant literature and ethical considerations in clinical practice.

It was late on a ‘full moon’ night in the emergency department — a phrase the ER staff used to describe unusually chaotic shifts — when a person emerged from the sea of blended patients occupying every inch of the emergency room.

Upon first glance, I had not noticed them walk into the waiting room. A closer look revealed a wincing expression, squinting eyes, and a nervous glance that betrayed their discomfort with the surrounding turmoil. The air of the emergency department was tense with high acuity cases, nurses running in between rooms, and the chanting of different patient names by ER technicians.

The person’s expression reflected a deep unease, likely stirred by the overwhelming tension and palpable trepidation around them in the overcrowded, understaffed emergency room. The patient remained in the doorway after registering, with no available seats to rest in.

After helping three other patients, I was finally able to call them forward for triage. There, I gathered a better understanding of the journey that led them there, which unraveled in fragments.

With a voice that carried the weight of the day, they began, “Earlier today,” talking slowly and seemingly distracted, “I went to a different hospital… my head was pounding like never before. But I could not stay there, the line to see the doctor was out the door.”

The sight of the overcrowded waiting room compelled the patient to leave — not simply due to the looming wait, but because it signaled uncertainty about when, or even if, they would be seen at all. Hours passed before they sought care again, this time at our ER, when they began to experience a loss of vision.

Suspicions were raised for a stroke, although there was no certainty yet. A CT head was ordered, however, there were also other critical patients in line for our only usable CT scanner in the hospital, including someone who had suffered from cardiac arrest.

“We may have to wait some time to get to the CT scanner,” I said.

As the patient heard my words and they transformed to understanding, I remember seeing the pinch in their eyes and a fall of their countenance from being in a place as daunting and unfamiliar as the ER, in addition to being asked to wait longer than time would allow if they were subject to a stroke.

The patient’s eyes first called for attention with a loss of vision but spoke beyond to testify to a truth that extended beyond their symptoms: the healthcare system is stretched to its breaking point. Stroke care depends on urgency; every moment of delay leaves a trail of irreversible harm. Yet the patient’s first encounter with care demanded waiting — a cost that they, and their body, could not afford.

In the reality of medical practice, clinical care is often out of reach for those who encounter the barriers of time and access. Many regions of the United States, like the Inland Empire of California, are medically under-resourced in hospital beds, machines, and primary care prevention, where patients may have to travel far distances to hospitals, or delay seeking treatment.

The patient’s eyes didn’t have the luxury of waiting, and the potential stroke would not pause for permission. The patient’s decision to leave the first hospital wasn’t about impatience — it was about survival in a system that too often demands patience from those least able to give it. This is not just one patient’s story. It is the story of a system that asks patients to navigate overcrowded ERs, interacting with overburdened physicians, and an isolating infrastructure.

In a national survey conducted, approximately 91% of ERs in the United States reported overcrowding as a problem. In addition to understaffing, overcrowding has been shown to affect quality of care and increase the risk of adverse outcomes for patients.

The patient’s blurry vision reminded me that the eye is more than a window into the body; it is a mirror reflecting the system itself. In the words of Charlotte Bronte, “the soul, fortunately, has an interpreter–often an unconscious but still a truthful interpreter in the eye.” This patient’s eyes interpreted the haziness of the path to quality healthcare.

Every patient who walks away from care because of overcrowding or long wait times, carries the weight of a fractured system. Every delayed diagnosis reflects not just a medical pitfall but a societal one. The resources to prevent this progression exist, but the infrastructure to deliver them falters. That day, I found that the patient’s eyes challenged what they saw, and motivated me, as a call to action for those who have the power to change.

Additionally, the eye can mirror the system itself, but also those who look into it. Looking into this patient’s eyes, I felt the burden of powerlessness not only for the adverse circumstance, but as a participant in healthcare. In this mirror I saw a reflection of a certain helplessness in my inability to fulfill the most basic duty of care, which is empathy in full due diligence.

To listen and understand an individual is common sense, but it is often met with pressure of a looming hidden curriculum to prioritize efficiency over depth of patient care. While I should have provided a deeper and more satisfying explanation of the circumstance to this patient, I had to move forward to keep the timeliness and pace of the ER.

The feeling of powerlessness in healthcare is a reciprocal phenomenon — experienced by both those receiving care and those providing it. It is a cycle characterized by patients’ feeling helpless in their vulnerability, and healthcare professionals struggling to offer the care they know is needed due to external pressure and lack of control in tragedy.

In Henry IV, Part II, William Shakespeare wrote, “I see a strange confession in thine eye.” As professionals in medicine, we must be attuned to these unspoken confessions. The confession of powerlessness, born of a failing system, is one that affects both patients and clinicians profoundly.

By looking into the eyes of those we care for, we can recognize when a sense of powerlessness arises — a feeling that must be acknowledged and addressed appropriately. The desire to aid people in relief of their pain is not wrong, but not always possible in the manner we wish to in a strained system.

However, the patient’s experience of powerlessness within the medical industrial complex is a confession we can confront. Whether this is achieved by developing innovative solutions for quality improvement, advocating for hospital policy change, or prioritizing a time to educate patients, we can tune into action for better a clinical experience.

Recognizing the limitations patients face will further allow us to increase our understanding of their unique pain and reflect on such changes needed to improve their experience. By acknowledging these challenges, we can endorse a better system of healthcare delivery — one that not only treats illness but also empowers patients to regain a sense of control and dignity in their care.

I would like to thank Dr. Noriko Anderson and Isabel Moh for their creative contributions to this piece.